Just when I thought I had finished opening all of my Christmas presents, Sight & Sound released their annual poll of the year’s best video essays! Read and watch here.

This year’s list was co-edited by Ariel Avissar, Grace Lee, and Cydnii Wilde Harris, and features 170 unique recommendations from 42 practitioners of the form. Congratulations to Ariel, Grace, and Cydnii, and all of the essayists who had their work(s) selected, and the contributors! As always, I am eager to explore the list in more detail and watch the videos that did not come across my radar this year.

I am also deeply grateful to Ariel, Grace, and Cydnii for the more than generous shoutout they gave to me, The Video Essay Podcast, this newsletter, the videographic exercises created by listeners, and the Black Lives Matter Video Essay Playlist in their introduction to the poll.

For those who may not be familiar with the poll, this is the fourth year Sight & Sound has published a survey of the year’s best work. You can find past polls here: 2017; 2018; 2019. I had the honor of co-editing the 2019 list with Ariel and Grace, who also joined me for an episode of the podcast dedicated to the list. We have something similar in the works, so stay tuned!

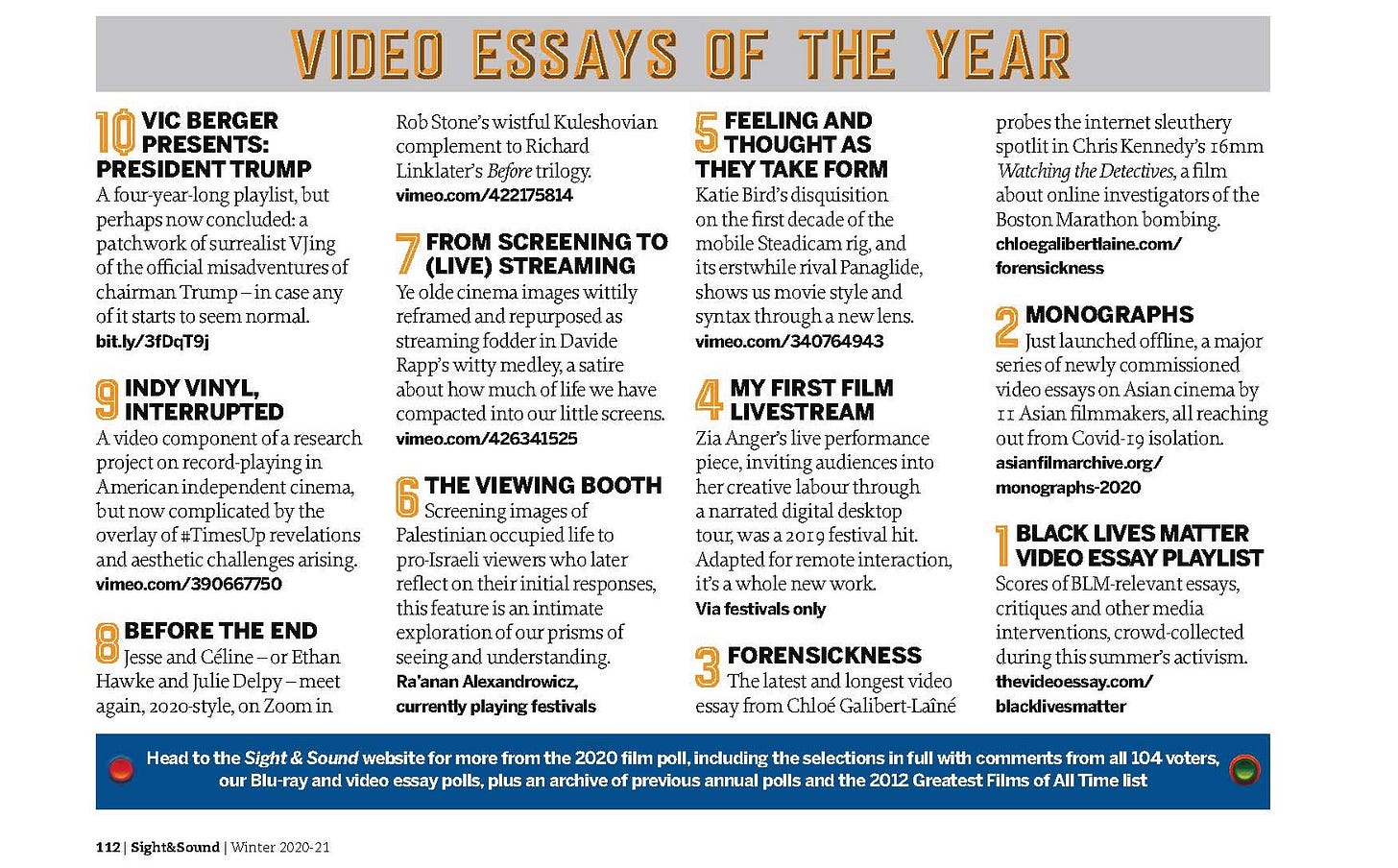

This year, the Winter 2020-2021 print issue of Sight & Sound also features a kind of “editors’ picks” of the year’s ten best works. Nick Bradshaw, the magazine’s web editor, described the list in a tweet to Catherine Grant: “You’re looking at what we might call an educated guess at a preview of the practitioners’ poll, which was still in the works when we went to press.”

Needless to say, we’re incredibly honored that the Black Lives Matter Video Essay Playlist is at the top of the list. As I wrote on Twitter, curating a playlist is pretty easy, the real work and skill is found in the collected videos. I hope that more people will continue to watch, enjoy and learn from what's on the playlist after reading about it in Sight & Sound.

As one of the contributors to this year’s poll, I figured I would end what may be the last newsletter of the year with my picks! Of course, there are so many video essays that I could not include, and the list reminded me of even more that I could have included! I may do a follow-up to this list in the coming days, but in the meantime, here are picks. But first, some thoughts in what is (I think) the longest newsletter to date!

I’ve never been able to view any list the same after reading Elena Gorfinkel’s essay “Against Lists,” published in Another Gaze. I don’t remember how or where I first encountered the piece, but I think I first read it around the time we began curating the 2019 list. Anyway, I don’t have much to add other than I think it’s useful to read (and re-read) the essay whenever a big list is making the rounds. As Gorfinkel writes, “Lists are for laundry, not for film.”

As I’m sure is true for many people, I tried to have my picks reflect my own adventures in video essay-watching this year. I did not search out new video essays after receiving the invitation to contribute, and instead drafted an initial list of ten or so video essays from memory in an effort to have my selections truly reflect the videos that most resonated with me throughout the year. At the risk of sounding too self-centered, I wanted my list to at least partially say something about me and the year I’ve had. After all, one of the reasons the list is so invaluable is because we not only get an array of video essay recommendations, but we also get to see who and what other video essayists are watching and learn from how they think and write about videographic criticism.

I consider myself a video essayist, but this year, for me, has been about realizing that the place I occupy in this community is not, primarily, as a video essayist. In 2019, I released a few videos (and created a few more that remain private), but in 2020 I did not really create anything other than a few videographic experiments and exercises. I also finalized a fanvid I began in 2019, “That Fabulous Lady,” which is a celebration of Mrs. Danvers and is included as part of my ongoing project, Seeing Truffaut’s Hitchcock.

Apart from finishing a written master’s thesis on Adam McKay, my main focus this year has been the podcast and its various branches: organizing the homework exercises assigned to listeners; the regular curation involved in the production of this newsletter, including interviews with student video essayists; The Journeys of Cary Grant; and, of course, the Black Lives Matter Video Essay Playlist with Kevin B. Lee and Cydnii Wilde Harris. The only “videographic” project I worked on this year is my ongoing “Rio Bravo Diary” which, as I’ve said here before, I’m not entirely sure is videographic criticism.

There are moments when I wish I had carved out more time this year to create a video essay or two. But this year I have deepened my passion for conversation and developed a new one for curation. I love the fact that the podcast and this newsletter have become conduits for the creation and sharing of videographic work, and I hope to continue to expand that work in 2021 and beyond. And so, as I went about making my selections (contributors to the poll are allowed no more than seven), I knew that I wanted to draw a majority of my picks from the Black Lives Matter Video Essay Playlist and the works of students I have interviewed as part of this newsletter (all of which can be found here).

Meshes of the Afternoon is a film I found myself rewatching again and again in 2020. This is in part due to the fact that I had the good fortune of reading Maya Deren’s writings for the first time this year at Cambridge in a course taught by John David Rhodes. I was also inspired this year by Cristina Álvarez López and Cristina’s students. In February, Cristina published a post on her website, Laugh Motel, entitled, “Playing with MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON.” The piece is partially a reflection on assigning students in her course on audiovisual criticism a practical exercise in which they were required to use Meshes of the Afternoon. In her post, Cristina writes, “I’m in favour of films with a short running-time, because they are more manegeable in the editing timeline and students can come to know their source better; this also happens to be a great film that offers wild possibilities for re-editing, and lots of ideas about unconventional ways of treating your material.”

After reading Cristina’s post, I began searching for more videos on Meshes of the Afternoon and considered playing around with the film myself in Adobe Premiere. So you can imagine my delight when I first saw Alex Slentz’s video essay, “It’s Back Luck to Compare Hands.” Among the most well-crafted video essays I have ever watched, Slentz’s video had me rethink the way that video essayists treat their canvas, as I wrote in the poll:

Meshes of the Afternoon is one of those films that I rewatch all the time, just to try and understand how it works; how it was assembled. I feel the same way about Alex Slentz’s video, which blends together footage from Maya Deren’s film, Persona, and Un Chien Andalou. Similar to the video by Probst and Hann, I am inspired by the way Sletz allows us to see the canvas on which the video essay was created. The fluid movements of the images and their interactions with one another blend together in a beautiful collage and insightful analysis.

I interviewed Alex Slentz for this newsletter in July and was particularly interested to learn that Alex did not intend to create this video as a ‘video essay’ but instead as a filmmaker operating within the found footage tradition. As Alex told me at the time, “For me, the tradition of found footage has been to utilize found footage to create new works, while video essays were to make a commentary on specific films or genres. When discussing this certain piece however, seeing how it utilizes found footage and compares surrealism in them, it definitely falls in line with what I’ve viewed as video essays.” One of the joys for me of the S&S poll is that it collects a range of works under the banner of ‘video essay’ and brings them into conversation with one another, so, including “It’s Bad Luck to Compare Hands” was a no-brainer.

(P.S. My apologies to the late Alexander Hammid for not crediting him in my commentary on the poll!)

In October 2019, I traveled across the Atlantic for the first time to attended a master’s program at the University of Cambridge. I was excited, but scared as hell. Apart from a weekend with friends in Montreal, I had never before left the United States. And if you had told me two years earlier that I would be pursuing a master’s degree in Film Studies, I would have thought you were out of your mind. At no point did I regret my decision (I was lucky enough not to have to pay a dime for the education), but such life-changing events naturally lead one to question one’s choices. A few months prior, I had rejected a dream internship in favor of attending the program (and also video camp).

I first stepped in a UK cinema a couple of weeks after I arrived, to see Portrait of a Lady on Fire at the Cambridge Film Festival. As I sat in the theater and watched Céline Sciamma’s film, I was overwhelmed with emotion. The beauty of Portrait of a Lady on Fire seemed to reaffirm every reason why I was/am passionate about the movies, and why I want to continue to study them forever. Around this time last year, Film School Rejects, where I am contributor, put out their list of the 100 best movies of the decade. I wrote the blurb on Portrait of a Lady on Fire and called the film my favorite of the decade. Is it actually? Maybe. But, similar to the way I approached selecting videos for the S&S ballot, Portrait of a Lady on Fire marked what was probably my most personal and memorable movie-going experience of the decade, in addition to being a masterpiece in its own right. And one of the joys of 2020 was watching the film become the subject of video essays. (I’m currently at work on a round-up of video essays on films by Céline Sciamma, so if you have any recommendations please let me know. I’ll publish the list as a ‘guide’ in this newsletter later next year!)

Perhaps the finest example of a video essay on Portrait of a Lady on Fire I saw this year was “Tear Away, Turn Back, Breathe” by Martina Probst and Chantal Hann. The video was sent to me by Kevin B. Lee and created in a workshop taught by Michael Baute, who required all students to work with Portrait of a Lady on Fire. I interviewed Martina about the piece, and asked if there was something about the film that makes it so suitable for videographic work. “Thematically the film is about two women and their love relationship in a conservative surrounding. With that narrative the film exploits grand questions of cinema itself: questions of the gaze (the seductive force of the gaze), the relationship between the bodies in space, of hand (gestures) and object, and so on and so on,” Martina said. “There is definitely something about the film that is meta-cinematic or essentially cinematic and therefore makes it a prime candidate for cinephile fetishism.” Here’s what I wrote about their video essay:

Over the past nine months, I have tried to relive my favorite pre-pandemic moviegoing experiences through video essays. This video by Martina Probst and Chantal Hann, two students at the Lucerne School of Art and Design, is among the finest analyses of Portrait of a Lady on Fire I have seen. But what I find so compelling about their essay is their willingness to at times forgo images entirely and embrace a blank canvas: the black screen. Video essayists often feel the need to fill every second with images. Perhaps we should allow our work to, like Marianne, breathe.

My next two picks were selections from the Black Lives Matter Video Essay Playlist. Collaborating with Kevin and Cydnii on the playlist was one of my personal highlights of an otherwise awful, scary, and overwhelming year. We have an episode of the podcast in the works dedicated to discussing the playlist in more detail, so I’ll leave much of what I have to say about those works until that conversation. We’ve also had an opportunity to discuss it in a variety of settings, including at the Open City Documentary Festival and the Camden International Film Festival.

But I will just add here that these two works, “Unlocked” by Jazmin Jones and “cops ordering food” by Manny Fidel, were not created as ‘video essays.’ Jazmin is a video artist and Manny is a columnist and editor for Business Insider, who posted his video to Twitter. In addition to exploring the role that videographic criticism can play in illuminating racial and economic injustice, the playlist, like the S&S poll, challenges many preconceptions of what a ‘video essay’ is and can be. These two works, in addition to being powerful videos in their own right, do just that.

I think about “Unlocked” by video artist Jazmin Jones often. In an interview, Jones described the way she shifted the focus of the appropriated videos away from the white people at the centre: “It was a matter of zooming in… trying to reframe so that we’re really focusing on the pleasure and the experience of the black fems.” Jazmin may not have set out to make a ‘video essay’ when she created “Unlocked,” but the way she manipulates the footage is among the most powerful examples of the form I have seen.

I can’t do justice to Manny’s video in 100 words. It’s hilarious and deeply insightful. I also love his follow-up tweet: “I made this in like four mins do NOT comment on its quality.” Manny’s video was made three weeks after the murder of George Floyd, at a time when a narrative emerged in the United States that police officers were somehow the real victims in society. The video makes a mockery of that absurd notion and, in the process, shows that a definition of ‘quality’ as it relates to videographic criticism is far more nuanced than one might think.

My next pick was pretty easy. Getting to be “in the audience” of one of Zia Anger’s live streams of My First Film was among the highlights of my year, and without question my favorite screening of any kind in 2020. I wrote an essay about my experience with the film for Film School Rejects (which I reprinted in this newsletter), so I’ll just leave you with what I said in the poll:

My First Film debuted in 2019 as a live film performance; an innovative desktop documentary that earned high praise in last year’s poll. Unable to perform in person this year, Anger began streaming live performances throughout the spring. The work continued to break ground and morphed into something new, a film that reflected Anger’s own pandemic experience. During the performance I saw, Anger texted her dad to say she loved him. Watching My First Film during such frightening times was a cathartic experience, one that made me briefly feel like I was back at the movies among friends and strangers.

Liz Greene, a former guest on The Video Essay Podcast, summed up my feelings about the next video in the her S&S ballot: “If I could have made any other audiovisual essay, I wish it could have been this one!” Indeed! After the first time I watched Johannes’s video, I knew I would include it on my list. It’s a stunning piece, and yet another reason why I am continually fascinated and inspired by Johannes’s work, as I wrote in the poll:

If there is one video essayist whose style and sensibility I most try to emulate in my own work, it is Johannes Binotto. His videos are rigorous and scholarly, yet deeply personal and emotional. In this video, like much of his work, Johannes turns his cinephilia into a shove which, like Lisa Fremont, he uses to dig deeper and deeper into the fabric of Rear Window. Follow the Cat gives us a new way of understanding familiar images, and thus gets at the heart of what videographic criticism is and what it can do and be.

And finally, we come to a work that I will continue to revisit again and again in 2021, Ian Garwood’s “video monograph,” Indy Vinyl: Records in American Independent Cinema: 1987 to 2018. I’ll be interviewing Ian on an episode of the podcast early next year, so I’ll save most of my thoughts for that conversation. But heading into 2021, I hope to think more about what it means to write about videographic criticism, and in particular specific projects, videos, and video essayists. It’s why I was so excited to publish Alan O’Leary’s essay on Matt Payne’s video essay, “Who Ever Heard…?,” as part of this newsletter back in July. Reading Ian’s article in NECSUS was incredibly illuminating for me, and had me thinking about the ways in which we talk and write about our own work and the works of others, which, after all, is why I started this newsletter in the first place! And I’m particularly excited to read Ian’s upcoming essay, “Writing About the Scholarly Video Essay: Lessons from [in]Transition’s Creator Statements,” which will be published soon in The Cine-Files. My final pick:

Another ground-breaking work this year came in the form of Ian Garwood’s “Indy Vinyl: Records in American Independent Cinema: 1987 to 2018,” a project that features a range of video essays and written works. One aspect of video essay-making that often gets overlooked is the amount of time dedicated to making each and every video. Ian’s project, both in size and scope, but also given the fact that he released parts of this project as they were finished, beautifully captures the labor of love that is video-essay making, all while pushing the boundaries of what the form can be.

Finally, thank you all for a wonderful year!! See you on the other side. Peace.

News & Notes

Have something that should be featured? Email me: willdigravio@gmail.com

The latest issue of NECSUS is here! The issue includes the first of two sections of audiovisual essays on sound and music in film, edited by Liz Greene. The first section features essays by Liz, Jaap Kooijman, Oswald Iten, and Cormac Donnelly. Read and watch here.

Issue 6 of Tecmerin is also here! Watch and read here.

I was honored to contribute a video to Learning On Screens’s “Introductory Guide to Video Essays.” I discussed video essay dissemination. You can watch the video here.

Meg Shields at Film School Rejects curated a list of the “20 Best Video Essays of 2020.” Read here.

To celebrate Lucrecia Martel’s birthday, Catherine Grant curated a Vimeo showcase of videos on or by Lucrecia Martel. Watch here.

Jaimie Baron, the author of Reuse, Misuse, Abuse: The Ethics of Audiovisual Appropriation in the Digital Era, was interviewed earlier this month by Bruno Guaraná in Film Quarterly. Read here.

Kevin B. Lee has joined Twitch! On December 12, Kevin streamed himself live-editing a video essay. Watch here.

I’ve been an assistant editor of Screenworks now for more than a year, and was recently “promoted” to associate editor, where I’ve started handling submissions! And to remember all of the works the journal has published in the last year, I put together this short celebration reel! Watch here.

Student Spotlight: Elizaveta Gushchinskaya

Is there a student(s) or former student(s) of yours you would like to see highlighted? Email willdigravio@gmail.com.

Elizaveta Gushchinskaya created this video essay at the Polish-Japanese Academy of Information Technology within the workshop on video essays under the supervision of Leigh Singer.

How did you come up with the idea for this project?

The workshop with Leigh Singer was organised during the lockdown and was conducted online. In a week's time we created projects focused on the idea of ‘Them and Us’ within the topic of pandemic. It’s of course the vivid experience of the present-time that shaped my work which can be read as the recording of the experience, as a memento of feelings, challenges and concerns one might have experienced during these troubled times. When the “real world” has come to a halt most of us found ourselves being glued to the monitors in our spaces. New Normal is the depiction and my own interpretation of the many issues related to the lockdown. By recognising the ways in which the experience affected us as well as created our new realities and how we delivered something new from these realities — I ended up with a videographic work that covers up a wide range of topics.

How did creating a video about, as your title says, the "New Normal" impact your own experience with the new normal? In other words, what was it like to make a video about quarantine and coronavirus as you were living in that very moment?

I think that each and every one of us has a very individual experience of the lockdown and a unique story about navigating the new pandemic-dominated life scenario. I remember how at the very beginning of March 2020 I started receiving multiple emails from the academy about the cancellation of classes — in Warsaw, the winter semester just started then. In the first couple weeks of March, no one really understood how bad the situation would get and how long we would be in quarantine. When things started to get serious I managed to get a flight back home directly from Warsaw to Minsk. I was based in my hometown during the period of quarantine, Belarus hadn’t imposed any lockdown measures or social distancing rules during the pandemic and everything continued to function as normal. The situation differed a lot from the rest of the world. In a sense, my own experience was mostly concerned with a sudden switch to the remote format of studies. So I could sort of observe from a distance how new realities were shaped for others and always had a chance to interact a little bit with these new born realms without being particularly engaged within them. The position of an observer allowed me to better notice and realise an overall impact of the overwhelming situation. It was and still is really interesting to see people’s reaction and adaptation to the disruption of familiar realms in which we lived for a long time. I try to think positively because things will definitely go back to normal, but afterwards the change will still be present in our newly shaped world.

Your video asks many questions of the audience. Why did you choose to structure the essay in that way? How have people who have seen your video essay responded to it? In other words, have they provided answers to the questions you pose?

The genre of a video essay is very flexible. It allows an experimental approach to it, so I had a chance to improvise. I wanted to leave space in my work for the viewer to engage. I decided to do this very thing by simply asking questions. The point was to explore the ways in which we express and connect through our screens as well as to reflect on the many challenges we have experienced. I didn’t want the viewers to say what they think they should say — but to communicate, to deliver honest unvarnished answers, at least to themselves. Questioning things was also a great way to acknowledge our confusion. Responses I got suggested that people related to the issues I raised. Some of the questions my video asks can also be taken as statements of the lockdown paradoxes.

How did you go about choosing and assembling clips? You use a wide range of films and I'd be curious to learn more about why you selected the ones you did.

The introductory part of my video essay is based on the idea of how in real life you never see yourself but only those around you. I figured that I could visualise this extraordinary state by creating a sequence of clips in which cinematic characters confront their own reflections. In other words, it was not so much about the type of movies that I selected but about the act of confronting your real self in the mirror. But of course, each clip in the sequence evokes different associations and feelings such as embarrassment, anxiety, vulnerability – in short, the full range of emotions that we might have experienced during the lockdown. The real challenge was to find the right rhythm and meaning that would connect selected film clips into one whole. It took several revisions to achieve that goal and Leigh’s help in the process was invaluable.

The second part of my video essay is built around the contrast of ‘before’ and ‘after’ the lockdown and introduces various crowded scenes as a reference to the pre-pandemic world. Here, I tried to also utilise the evocative functions of music and sound. The track I use is Biosphere's Phantasm. It creates the atmosphere of a dream – through both the lyrics and the score – and connects clips to one another. ”We had a dream last night. We had the same dream” - was just something that echoed inside of me when I created this project, as all of us sort of experienced the same dream that in a blink of an eye became our reality.

Drawing on the contrast between fantasy and reality, I start the second part of my video with a clip of a young couple getting married on Zoom intercut with comic scenes from wedding movies such as Bride Wars etc. In my mind, weddings are an important, emotional social gathering that is not only about the physical presence of the most loved ones but also about a very specific way of dressing up and human interactions including dancing, drinking, and talking. The pandemic made those gatherings as we know it impossible. Yet, people were able to find an alternative, virtual way to perform them, which can be taken as an attempt to ignore current reality.

One of the cinematic examples depicting big social gatherings and the elusiveness of reality can be found in The Great Gatsby, as the film oscillates between dream and reality leaving the viewer uncertain about what is real and what is not.

Leigh also suggested to include to my video essay an absolutely incredible cinematic work – Ingmar Bergman’s Persona made in 1966. The opening scene of the film depicts a boy waking up from a dream, trying to touch the surface that can be perceived as both a movie screen and a mirror.

Both films take up the themes of the dream and make a visual statement about the elusiveness of the reality behind the screen which one might experience at a certain point.

The references to Netflix series American Crime Story and Unorthodox intercut with live performances and an online photoshoot introduce the idea of cultural consumption. We are all addicted to the amusement that capitalism has created to keep us comfortable and engaged. Being stuck at homes is an opportunity to engage with culture in new and maybe even more meaningful ways. For me, it’s really interesting to see what emerges from the current uncertain times.

New Normal culminates with a comical video of people having parties on Zoom. Here, I highlight the optimistic side of the realities that we create, because at the end they are the ones most worth exploring.