The Clock's Press Images: Some Thoughts

The Video Essay Podcast returns w/ Jason Mittell on The Chemistry of Character

At the end of last year, I had the chance to attend one of the epic, 24-hour screenings of Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Because the supercut of clocks in cinema and television takes place in real time, those interested in viewing The Clock whenever it is on display are restricted to whatever hours the hosting venue is open to the public. Thus, when Marclay sold copies of The Clock (for more than $460,000!) he stipulated that any public showings of the work must include at least one 24-hour showing.

In the latest issue of Cineaste, I have an article reflecting on my experience at the epic screening. I started at 7pm and lasted a little more than 16 hours, covering the entire time that MoMA is not typically open to the public. The bodily calls for food, coffee, and sleep became too much. When I left, I told myself that I would return for the final eight. But, as I discuss in the article, I have yet to do so.

When writing my article, though, I encountered something curious. On the museum’s press site, and indeed on other official press sites for The Clock, where additional information and images about the work are often housed, I noticed something. See if you can find it:

The images above are credited as “Still from The Clock.” This is, of course, perfectly legitimate, as I have no doubt that they are, in fact, stills taken from The Clock.

Yet the credit lines raise an interesting question about — and window into —the nature of remix. Devoid of the captions, these images would, of course, function just as well as stills (albeit perhaps resized) from the original films, which are, from left to right, Oblivion (1995), 8 1/2 (1963), and Metropolis (1927). What to make of this?

I think there is an important political point to be considered in the exclusion of the original film titles (whether this is deliberate, I do not know). What I mean to say is that in their exclusion, one sees an implicit defense of remix culture, of the belief that these stills are, in fact, taken from a totally new work, one that has transformed existing works into something new. Together, they become The Clock, and it is from The Clock these images are taken.

But as I started to write the captions for the images, something felt off. I felt a responsibility to identify these original images. The words of William Wees came flooding back into my mind. In Recycled Images, Wees writes, found footage “invite us to recognize it as found footage, as recycled images.” The stills mostly remove the context, removing a chance for that moment of recognition that is so obvious when actually watching The Clock. Thus, when I wrote my captions for Cineaste, I cited the original films, drawing on this incredible database of all films included in The Clock, accompanied by stills.

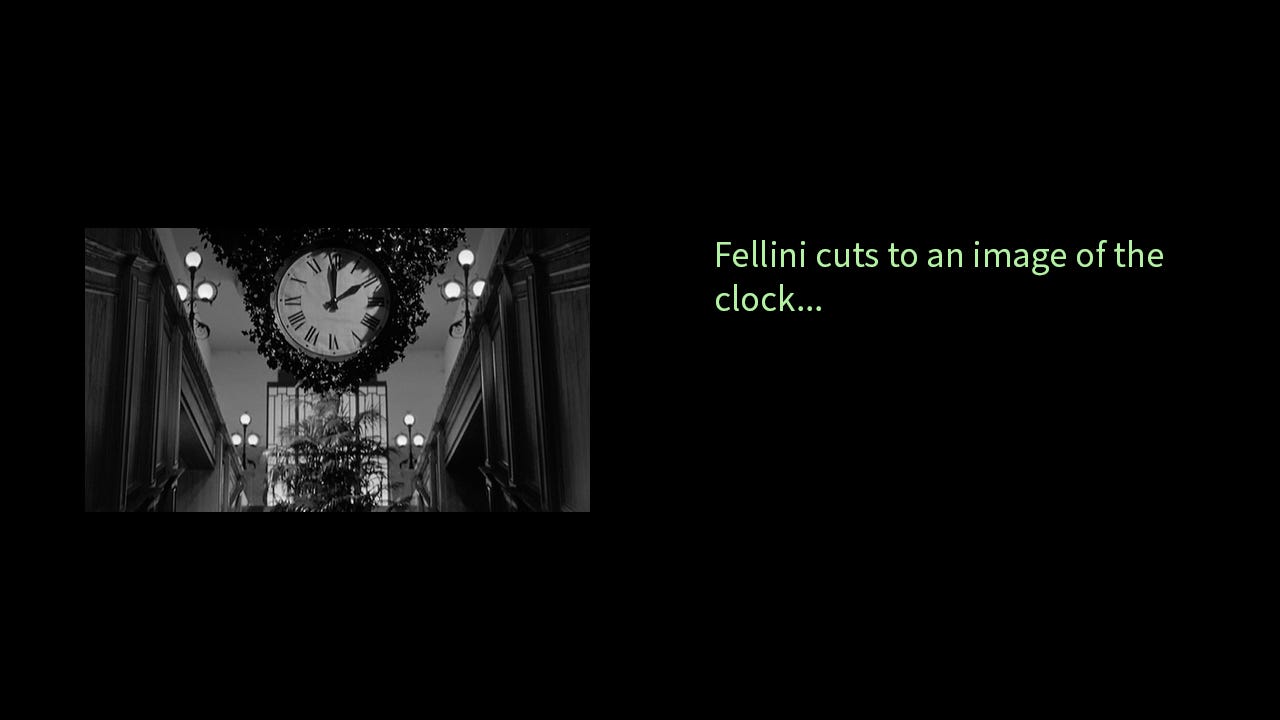

This got me thinking about how I might approach this were I writing about other video essays and drawing stills from them. I think it would depend very much on this moment of recognition and whether such a moment would carry on from the video essay to the still. For example, if it was something like this:

I would feel quite comfortable not making explicit that this still is from 8 1/2 and instead only citing the name of the video essay. While technically both original works cite their sources, and a quick search would tell an unknowing viewer that The Clock is a found footage work, there is something about that moment of recognition, of actually seeing the found-ness, that makes the stills from The Clock feel quite different. What do you think?

I’m teaching a course!

I’m thrilled to be offering once again my course, “Video Editing & Film Montage” at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The course is a basic introduction to Adobe Premiere Pro through the lens of film theory and remix culture. It is open to anyone outside the university and might make the perfect introduction to someone looking to dip their toe into videographic criticism. It is truly meant for beginners!

Enrollment is still open, so please consider sharing with students and colleagues, or perhaps even taking the course yourself! The course description is here, and information on how to enroll is here.

UMass is also offering the first ever grad certificate in Videographic Criticism, featuring a fantastic line-up of instructors. While my course is not part of that program, it might make a nice introduction to someone looking to pursue that course of study. Learn more about the certificate here.

What is a videographic book?

The Video Essay Podcast has returned! The longest hiatus in show history comes to an end with Jason Mittell, who joins to discuss his videographic book, The Chemistry of Character in Breaking Bad. The book is the first in a new series of open access, videographic books from Lever Press. Mittell joins to discuss the origins of the book and series, the philosophy behind a videographic book, and his longtime interest in alternative, open access forms of digital publishing. Listen and learn more here.

This is an abbreviated version of the newsletter. I hope to continue in the future rounding up notable video essay news, so please get in touch if you have something you’d like to share! Contact me: willdigravio[at]gmail.com.